One of the most common questions I get is this: how do you go home and share your game images the same night?

The truth is that it hasn’t always been that way. During the past year as I began to take photos at more and more games, I realized that I needed to become more efficient.

So I started testing and refining my process so that it was repeatable.

I consumed lots of articles and videos online to try to figure out how others did it.

Some of what I saw looked like it would work for me, so I gave it a trial run. Some of the advice I kept, some of it I modified, and some of it I discarded as not right for me.

Hopefully this article will give you some ideas that you might be able to incorporate into the approach that works well for you.

Be more selective during the game

When I first started photographing sports, I sat on the shutter button way too long and hit it way too often. It was the epitome of the “spray and pray” approach.

Of course, the more images that you take during the game, the more images you need to review, cull, and edit afterwards.

When you start out, it isn’t necessarily a bad technique because it helps you to learn how to be more selective. It isn’t just about hitting the shutter less and for shorter periods of time, but knowing when to start and stop your capture.

The only way to learn is by trying. Every game (even today) I pick one aspect of my craft to practice on or improve.

Now I am much better at recognizing when peak action is about to occur so that I don’t “waste” a lot of images.

Save images in JPEG format

Lots of people look down on JPEG format and tell you that you really need to photograph in RAW if you are a serious photographer. I used to be one of those people.

While RAW has its place, and I do use it occasionally for sports photos, I have learned that JPEG lets me work faster. In addition, when you are shooting low light sports (outdoors at night or indoors anytime) the built-in noise reduction with the camera is superior to anything you can do in post-production.

The other benefit of JPEG is that even on more consumer grade cameras, you are much less likely to run into buffering issues when capturing high-speed bursts.

Be ruthless when culling images

Depending on the sport, team, and the significance of the game, I will typically have anywhere from 1000 to 3000 images to process. (Unfortunately, just as I got pretty good at controlling my spray and pray impulses, I upgraded to a camera that shoots 20 frames per second so I get double the frames with the same shutter press I was using before.)

If I haven’t seen a team in a particular season before, I usually capture more images just to get a little coverage of each player. Later in the season, I focus almost exclusively on peak action or interesting plays/stories. Then in the post-season I ramp up again since those games aren’t an everyday occurrence for most athletes and their parents.

Just because I take a lot of images doesn’t mean that I keep a lot of images, though.

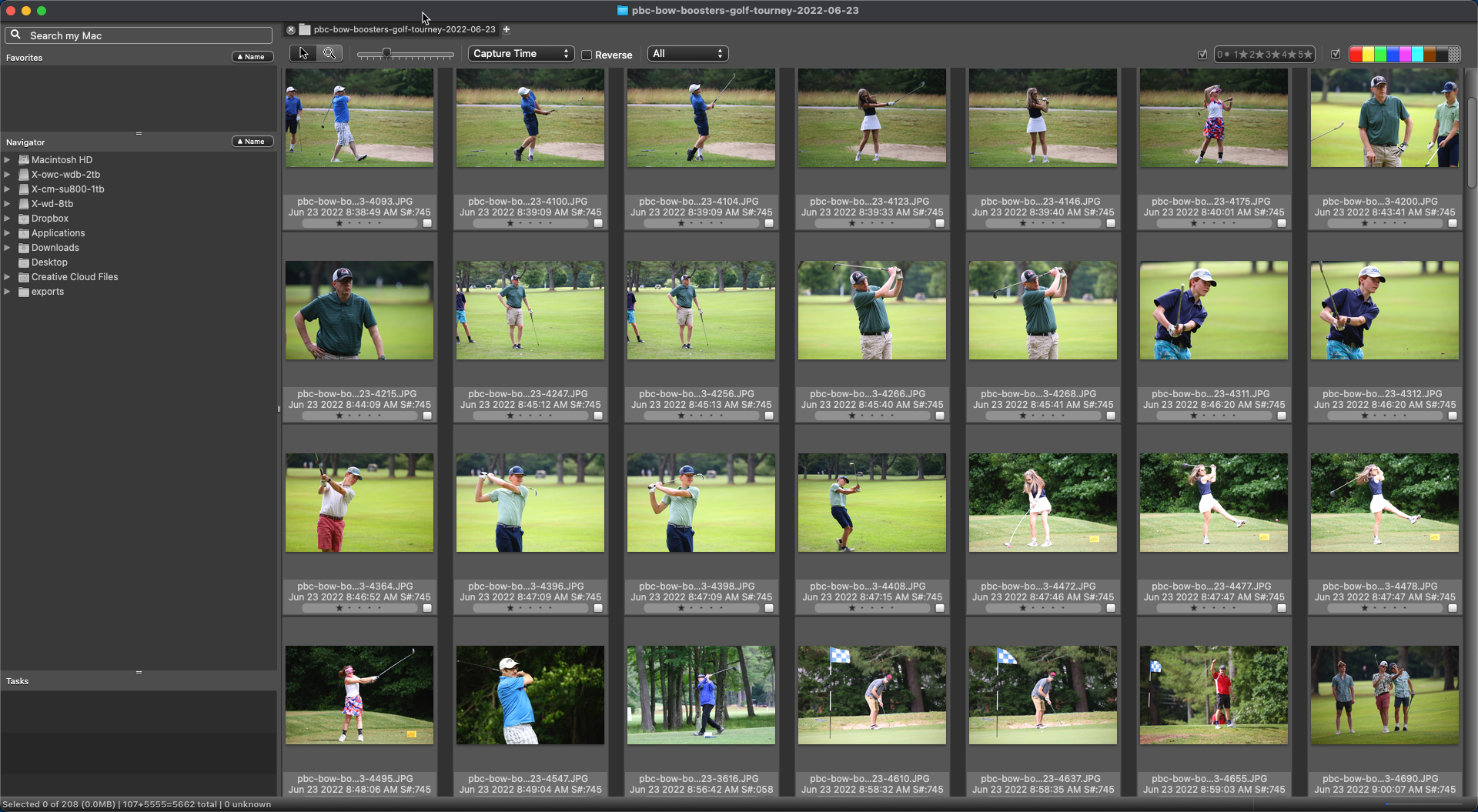

When I get home, I import all of my images into Photo Mechanic. This single piece of software has made a bigger difference to my efficiency than perhaps anything else I have done.

It turns out that most professional sports photographers also use Photo Mechanic, although they tap into far more functionality than I need. For example, they can use it to quickly tag and caption photos for distribution to employers or wire services.

In my case, the big advantage that Photo Mechanic has is that it produces images that I can review very quickly and makes it simple to move from one photo to the next.

I quickly go through all of my images and apply a 1-star rating to any of the photos that I want to keep and edit (if I have multiple games that I imported, I will use different star ratings for each game).

I have gotten pretty ruthless about my selections. I’m looking for action, eyes, ball/puck/etc., and context (opponents, goals, spectators, etc.). I try to grab only the best image of a play sequence, and I shy away from having too many of a single player that are too similar to others from the same game.

When I’m done, I filter for just the 1-star rated images (typically about 5% of the total images I captured — which makes sense since that would represent the best image from a 1-second capture at 20fps).

Those filtered photos now get copied to a dedicated directory on my hard drive where I import them into Lightroom Classic on my Mac.

Don’t overthink your editing

If I’m producing “standard” game photos for sharing online, there isn’t a need for lots of elaborate editing.

At one time, I did go down that rabbit hole and spent an absurd amount of time fussing over each image, adjusting exposure in specific areas, applying masks, and all sorts of other things that are best reserved for portraits or “special” game images.

Here’s how I handle the vast majority of game images:

- Straighten the horizon. A personal pet peeve of mine is looking at photos where it seems like the photographer was falling down when they took it. As much as possible, I try to find the horizon and level my images.

- Crop for impact. I am pretty aggressive about cropping my sports images. It is almost impossible to frame action correctly in camera since you are guessing where the players are headed, so I make up for it by chopping down my frame to just the essential elements and remove any distractions. I don’t care if I lose half the frame — modern cameras have plenty of pixels so you have lots of room to crop.

- Hit the Auto Tone button. Why do lots of manual steps if one click can get the job done or almost done for you? I would say that 98% of the time the Auto button in Lightroom Classic gets me almost exactly where I want to be. If not, I can hit Undo and go at it manually. In many sports, Auto may be the only thing that you need to do. In others — especially sports with helmets — you may need to tweak a bit to recover detail in the shadows created by those helmets.

BONUS TIP: I use the Loupedeck+ to help me be even quicker with my Lightroom adjustments. It is an unnecessary luxury, but it saves me time because I can just spin some knobs to adjust things like exposure, contrast, and saturation. There are other — even fancier — versions of the Loupedeck and similar devices that are worth considering if you are editing lots of images.

Keep culling while you are editing

The images that I selected in Photo Mechanic don’t all end up getting shared with the public. As I edit in Lightroom, I will continue to cull images that don’t quite meet my standards.

If I can’t get a crop that gives me an image I like, I drop the photo.

If I can’t adjust the image’s exposure or colors the way I want, I drop the photo.

If I noticed that the focus is softer than I thought on my first review, I drop the photo.

You get the idea. Continue to be ruthless.

I do this by giving a 5-star rating to any image I have edited that I plan to export, but I change it to zero stars if I want to skip it.

Find shortcuts

As you use your favorite editing software more, you will find that you can customize some of the actions to your own workflow.

Almost all of them allow you to assign commands to certain keyboard combinations so that you can get to the most-used actions quickly.

In my case, I have both Photo Mechanic and Lightroom set up to automatically advance to the next image as soon as I set (or change) a rating. It saves one mouse click or keyboard press, but every little bit helps when I have hundreds or thousands of photos to process.

Create an export process

Now that I have finished all of my edits, it’s time to share them with the world. Or at least the local community members that are interested.

I post my images to Facebook and SmugMug, with highlights shared on Instagram.

Here’s how I do it efficiently.

- Create export presets in Lightroom. I have presets for both Facebook and SmugMug setup so that I can quickly generate exported images in the right sizes and formats for those two services.

- Have a dedicated export folder. I have a folder on my hard drive that holds all of my game exports. It makes it easy to navigate to and upload to Facebook and SmugMug — and makes it easy to find again if one of those services has a hiccup and I need to retry the upload.

- Upload to both services simultaneously. I used to start the upload and stare at the screen until it finished. Now I start the upload to both at the same time and save a couple of minutes of screen-watching.

For Instagram, I browse the game gallery on my own website (via SmugMug) and pick the 10 images I want to include in a post for sharing on that service. Usually I pick one of my favorite images and then look for 9 more that have the same dimensions since Instagram forces all images in the post to have the same ratio.

Keep practicing and find what works for you

I’m still refining my process, but I have it to the point where I can cull, edit, and export most game photos in about an hour. Years ago it would not be unusual for to spend 2-3 hours or more on a single game.

As I noted above, it’s about finding what works for you. Just because it matches my approach to photography and helps me achieve the style of image that I’m looking for doesn’t mean that all of these things will work for you.

Hopefully there are some ideas or inspiration that you can take from this to help you become more efficient in producing your own sports photos.